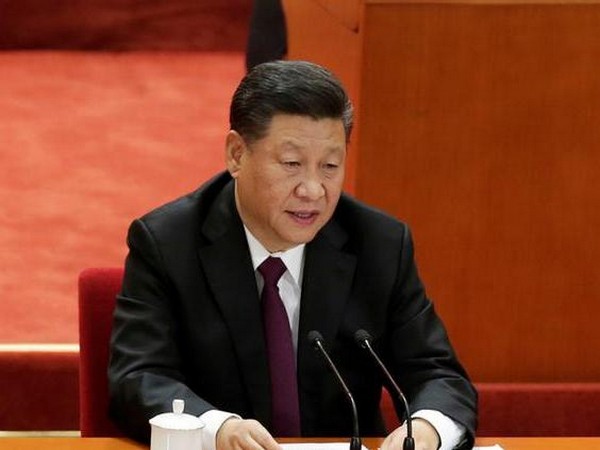

Chinese President Xi Jinping speaks at an event marking the 40th anniversary of China's reform and opening up at the Great Hall of the People in Beijing, China December 18, 2018. REUTERS/Jason Lee

Chinese President Xi Jinping (File photo)

Hong Kong, April 28 (ANI): Chairman Xi Jinping and the Chinese Communist Party (CCP ) are now facing a time of reckoning. Many had already been warning for years that China represented a dire threat to the world order, but Xi’s mishandling of the COVID-19 crisis and subsequent evasion of responsibility are looking like the straw that broke the international community’s back, say Western observers of China.

China may still sound confident, but this is a brash cover-up for serious domestic concerns. China was forced to delay the so-called “two sessions”, the annual National People’s Congress (NPC) that was due to take place in early March, as well as the meeting of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC).

This highly choreographed event rubber stamps government decisions and its budget. No alternative date has yet been announced, but since the CCP makes all decisions in any case, suspension of the NPC and CPPCC meetings makes little difference to governance.

Furthermore, the government typically spends its money first and only confirming the budget afterwards. Perhaps, this could be considered the advantage of a centralised authoritarian government! Nonetheless, symbolism is important to the CCP . Indeed, 2021 will mark the party’s centenary and it was even written into the Chinese Constitution in 2012.

Next year requires the attainment of two milestones in Xi’s “Chinese Dream of National Rejuvenation” – the “elimination of poverty” (raising incomes to an annual minimum of RMB2,300) and doubling the national GDP in comparison to 2011. Yet these goals are in danger.

Last year, China recorded its slowest rate of economic growth in 27 years. The pandemic will exacerbate the situation, especially with the threat of many countries pulling their global supply chains back home.

This explains why Xi is warning that China is encountering “a race against time to reach the Chinese dream”. Indeed, China is being hit hard where it hurts. It has attracted widespread criticism for imprisoning more than a million Uighur Muslims in harsh concentration camps.

Pro-democracy protests exploded in Hong Kong last year and this will be an intractable thorn in Beijing’s side. Then, Taiwan emphatically rejected Chinese overtures by returning President Tsai Ing-wen to power in January.

China is also facing stiffer resistance in the South China Sea, with the US military and others stepping up activities and rhetoric about China ‘s outrageous territorial claims. Furthermore, Xi’s flagship Belt and Road Initiative has lost its shine amidst accusations of debt-trap diplomacy. Instead of leading the world, China is finding itself at the sharp point of criticism, enquiry and global scrutiny.

Countries like Australia are calling for investigations into China ‘s bungling of the COVID-19 crisis, for instance, something that will be vigorously rejected by Beijing. Yet for a country and self-absorbed party obsessed with face, this is humiliating.

Writing a book soon to be published, Bates Gill, professor of Asia-Pacific Security Studies at Macquarie University in Australia, identified six drivers of Xi’s foreign policy. “Most have been long-standing aspects of China ‘s foreign policy. However, all have become much more prominent and vigorously pursued elements of foreign policy under Xi.

But taken together they offer a coherent framework for understanding – and responding to – China ‘s approach to the outside world.” Of the six drivers, he listed legitimacy as the core. He described it as “maintaining and strengthening the CCPas the sole governing party in China.

This key objective is realised through a foreign policy which keeps two target audiences in mind, those at home and those abroad. Abroad, the CCP looks to strengthen its legitimacy and survival by gaining the acceptance, appreciation and even approbation of foreign governments and societies for China’s system of governance, domestic policies and pursuit of overseas interests.”

Gill’s other five drivers that build on this are leadership (roles for Beijing on the international stage politically and in multilateral bodies), influence (projecting a positive image abroad and shaping others’ thinking about Chinese interests), power (coercive instruments of hard power), wealth (continued economic prosperity) and sovereignty (expanding China’s freedom for international strategic maneuver, plus protecting the territory it claims).

Despite current setbacks, Gill warned, “Increasingly prosperous, powerful and authoritarian, China intends to become a more intense global competitor economically, technologically, diplomatically, militarily and in the realm of ideas. The COVID-19 crisis will not change this.” However, upon examining Gill’s six drivers, it is easily seen that China ‘s image has been severely tarnished.

Both domestically and globally, Xi’s governance and standoffishness during the height of the epidemic in Wuhan is being criticised. China ‘s leadership, influence, wealth and legitimacy have all declined. To illustrate, China ‘s role in bodies like the World Health Organisation (WHO) is being looked into. China bought up global supplies of medical personal protective equipment, before later selling faulty and poor-quality equipment to others.

Its initial attempt to cover up the Wuhan virus outbreak and later clumsy propaganda to deflect criticism also backfired. China ‘s economy is suffering – shrinking 6.8 per cent in the first quarter alone – the first contraction since 1976.

A very recent Pew research poll found that Americans’ views of China have worsened considerably. Indeed, 66 per cent of Americans now look at China unfavourably, compared to 47 per cent two years ago. In the meantime, those in favour of China dropped from 44 per cent to 26 per cent in the same period. In the midst of all these setbacks, the few drivers it can rely on are sovereignty and hard power.

China insists the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) has been totally unaffected by COVID-19 infections, and it is business as usual as it moved an aircraft carrier task group through the First Island Chain, and a research ship began surveying the seabed of Malaysia’s EEZ with an entourage of China Coast Guard vessels.

As part of sovereignty measures, China on April 18 declared it had set up two new municipal districts to control the disputed Paracel and Spratly Islands. A day later, it published the Chinese names of 80 geographic and underwater features in the South China Sea.

With the rest of the world preoccupied with the coronavirus, China has trampled on others’ sensibilities and etched out its territorial claims more graphically. Malcolm Davis, senior analyst at the Australian Strategic Policy Institute (ASPI), tweeted, “Did anyone seriously expect China ‘s territorial ambitions to stop at invading and annexing Taiwan, and controlling the entire South China Sea and the East China Sea?

Or taking Arunachal Pradesh and Aksai Chin off India? They have big plans for the 21st century.” However, with China suffering, despite brave attempts to disguise it, a new opportunity is arising for countries to unite in their resistance of Chinese influence. This is the opinion of Professor Anne-Marie Brady, a New Zealand politics researcher at the University of Canterbury: “China is using the COVID-19 situation to push hard on territorial disputes in the South China Sea, to curtail Hong Kong’s freedoms, to force states to accept Huawei in 5G networks and to try and reshape the narrative of the origins of COVID-19 .”

She continued, “Yet China is politically weak right now, as many states are very critical of China ‘s mishandling of COVID-19 outbreak, which led to it becoming a global pandemic. Now is a good time for like-minded states to pull together and support each other economically and politically, and to rebalance their relationship with China .”

The narrative being peddled to the Chinese populace is simple. The coronavirus did not originate in China and, when it did spread, it was the failure of the local rather than the central government. In fact, the CCP responded extraordinarily well. Not only that, it has done better than other countries like the USA, and it can boast of its support of other countries. Highlighting the overall readiness of the PLA also stokes nationalist sentiment.

Yet China with its propaganda campaign and obfuscation has scored numerous own goals. Citizens and governments in Africa, Australia, France, Italy, UK and USA, for example, have reacted badly to Chinese insinuations. China ‘s “Wolf Warrior” diplomacy is hurting more than helping Sino-skepticism as well. Unfortunately, the world is going to have to face rising (ultra)nationalism by China and its citizens.

As the Chinese tabloid Global Times explained, “The days when China can be put in a submissive position are long gone. China ‘s rising status in the world requires it to safeguard its national interests in an unequivocal way.” Yet the world still struggles to understand the CCP and its nature. For example, Sinologist Professor Kerry Brown wrote a recent article discussing whether the CCP can be described as “evil”.

Certainly, Mao’s policies and paranoia killed millions, while Xi and his predecessors have grossly abused human rights and locked up millions of what they call “dissidents”.

Brown notes generally that, with 90 million members, the CCP is broadly representative of Chinese society in general, that it has changed dramatically since it was formed in the 1920s, and that it is not monolithic. He commented, “The most prudent thing one can say about the relationship between the [people and the party] is that they are very complex.

And if you want to start deploying language like ‘evil’ about the party, then you are going to have to start labelling a good number of Chinese people that way too. Party members are Chinese people, after all – not some separate species!” Brown continued, “There are many things it can be labelled. Autocratic. Sometimes in its decision-making inhumane.

Too vast in scale. Too laden with history. But the idea that its millions of cadres and actors are busying their lives just working on doing harm is risible. “The idea that [the Chinese people] are silent, suppressed and without agency is profoundly condescending.

Many of them may know their rulers are problematic and often incompetent. They are in good company there with people in Europe and the US. But they are also averse to radical and disruptive change. They have seen enough of that in their own history.

Maybe it is just a case of the ‘devil you know being better than the devil you don’t’. But to frame them as somehow cowed masses waiting for knights in shining armour to come from overseas is a colossal misjudgment.” However, a key difference to places like Europe and USA is that the Chinese people have no alternative to the CCP.

They cannot vote it out of power. Essentially, the modern-day CCP promised the Chinese people that it would make them rich, but the quid pro quo was that they would not be free. China has been on a collision course with the West for a considerable period of time, a path that accelerated under Xi as he deliberately ignored Deng Xiaoping’s dictum of “hide your strength and bide your time”.

COVID-19 is but a catalyst that has brought festering contentions to the surface. Indeed, the West has been found complacent, seduced by the promise of wealth and arrogantly thinking it would influence China for the better.

The USA and the West thought it was invulnerable and superior after having won the Cold War. That has proven a figment of imagination, as Beijing has foisted with growing zeal “socialism with Chinese characteristics” on a mostly unsuspecting world.

The world now sits at a critical juncture – how to be less reliant on authoritarian China but at the same time learning to live with it. Beijing thrives on the weakness of others, and for too long most countries have simply rolled over to Chinese demands. Perhaps COVID-19, as Brady suggested, is the perfect time to enact a rebalance. (ANI)