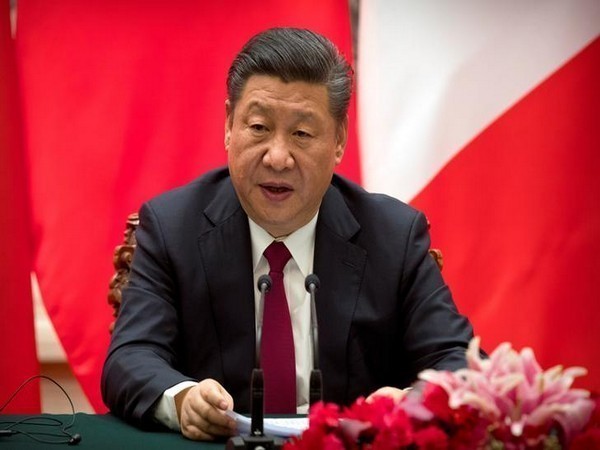

Chinese President Xi Jinping speaks during a joint press briefing with French President Emmanuel Macron, not shown, at the Great Hall of the People in Beijing, China January 9, 2018. REUTERS/Mark Schiefelbei/Pool

Washington [US], September 29 (ANI): Seeing the atrocities inflicted by the Chinese government on the Uyghurs, a Washington Post journalist recalls the constant scrutiny she and her team faced while they were in Xinjiang throwing light upon the crimes against the community by the Chinese Communist Party.

“It was the start of four days of intense surveillance and nuisance checkpoints designed to obstruct our reporting and ensure that local people were too afraid to talk to us. There were cars that tailed us everywhere and the Keystone Kops, men who would jump behind bushes or pretend to talk on their phones while obviously following us,” journalist Anna Fifield, a former Beijing Bureau chief wrote in the Washington Post.

In her piece, she further wrote that the Public Security Bureau officers “who repeatedly called us to the hotel lobby” to insist that the group followed local reporting regulations “that, among other things, required that we get anyone’s permission to interview them”. “Before long, we endured a farcical argument about whether we needed assent before we could photograph a public building,” she added.

Fifield said that the trip to Kashgar (in Xinjiang) was the “final reporting expedition” she would make after 10 years in Asia but it made her recall not her trip to China but a previous assignment in North Korea.

She described Kashgar as an “evocative city, the home of Uighur culture” that was once a stop on the Silk Road and “has been turned into a Potemkin village, like Pyongyang, where it’s impossible to discern where the real ends and the staged begins.”

Visting Kashgar as a tourist for the first time in 2006, she remembered it to be “a magical place of Uighur people who looked Central Asian and spoke a Turkic language written in Arabic script”.

“Before returning to Kashgar this month, I dug out my photos from that trip. I found pictures of the renowned Id Kah Mosque, abuzz with activity. Photos of men with beards and women with headscarves and young children smiling and posing for my camera. I wondered what had happened to these children, many of whom would now be in their early 20s,” the scribe wrote.

The Chinese government has detained over 1 million Uighurs in “in reeducation camps designed to strip them of their culture, language and religion”. The scribe wrote that in these camps the Uighurs had to shave their beards and uncover their hair.

“They’ve been made to pledge allegiance to the Chinese Communist Party. Children have been taken from their parents and put into orphanages,” she wrote.

It was when she returned to Kashgar that she was struck by how, “at first glance”, it seemed relatively normal. “In the Old City, families were out at the night market, eating piles of meat and bread. Kids could be heard laughing through open upstairs windows. There were even young men — prime targets for the detention campaign, which was ostensibly about deradicalization — on the streets again,” she wrote.

“Had any of the people I saw in Kashgar this month been affected by the “reeducation” campaign? Almost certainly. But I couldn’t ask them. Just as in Pyongyang, I didn’t try to interview people on the street or in stores, as I would do anywhere else in the world,” she added.

Had she interviewed one of the people on the street, she wrote that it would have put those people in danger. “I would have loved to talk to someone who had been through the camps — but I was conscious of the risks I posed to people if I tried to discuss sensitive subjects. Or talk to them at all,” she wrote further in her story in the Washington Post.

Writing about her arrival in China, while finishing a book on Kim Jong Un and “immersed in North Korea”, she said, “I tried to stop myself from looking at China through the lens of its paranoid neighbour. China is not North Korea, I told myself.”

But Xi Jinping taking over as president of China did not make it easy for the scribe to keep her thoughts about North Korea “at bay”. “There is still a level of latitude and commerce and vibrancy here that is unimaginable across the northeastern border, but some days China really feels like North Korea,” Fifield wrote.

“Not just in Xinjiang but across China, it has become extremely difficult to have conversations with ordinary folk. People are afraid to speak at all, critically or otherwise. Students and professors, supermarket workers and taxi drivers, parents and motorists have all waved me away this year,” she added.

But, every now and then, she wrote that she would encounter a “brave person” who wants to talk, and “I am always grateful to them for their honesty” but with that honesty comes a new layer of fear that whether her story would result in this person being detained. Those who speak out face severe consequences, including many years in prison.

She further wrote that it was clear that China now thinks the cost of having foreign correspondents — people who do pesky reporting on human rights abuses — outweighs the “benefit of having people to write about what a great destination China is for investment”.

“I don’t see the situation getting freer or easier for the Chinese people any time soon, nor for the foreign journalists who try to show their audiences back home what it’s like to be on the ground in China, for better or for worse,” she wrote further remembering a joke from an acquaintance, ” “We used to think North Korea was our past — now we realise it’s our future.” (ANI)